by Sam L. Savage

““It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it”

”

According to my new best friend and advisor, ChatGPT, the above quote from the 1906 book, “The Jungle,”

“reflects Sinclair's belief that the interests of capitalists often conflict with the well-being of workers and the general public, and that people will often choose to ignore or justify harmful practices if they stand to benefit financially from them.”

Although the context of the quote was

“the unsanitary and inhumane conditions in the meatpacking plants and the corrupt practices of the industry, such as the manipulation and adulteration of food products,”

it applies equally well today to

The unsound and inaccurate computations in the realm of uncertainty and the common practices in industry to use averages that introduce systematic errors, in short, the Flaw of Averages.

With a few notable exceptions business is conducted with single number estimates that pass between analysts (who know better), information systems and decision makers. Until now, you couldn’t just quantify uncertainty at one of these nodes and have it propagate through the organization. Those insisting on probabilistic representations were misfits, who might ultimately lose their salary. So many people know that this is wrong, however, that it has become necessary to ignore or justify these harmful practices.

Doug Hubbard is author of the How to Measure Anything series, the Failure of Risk Management, and other important books on quantifying uncertainty. As brothers in arms in the War on Averages, we have shared numerous examples of clients who are strongly motivated to not understand uncertainty. This has resulted in

The Savage and Hubbard Top Ten List

of Lame Excuses for Not Quantifying Uncertainty

But Sinclair’s quote reminds us that it is not just intellectual laziness and post traumatic statistics disorder (PTSD) holding people back, but also job security.

Financial Engineering and Physics

Financial engineering was a great victory in the War on Averages. In 1973, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes published “The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities.” It contained the famous Black-Scholes equation for pricing options that solved a specific case of the Flaw of Averages. It showed that valid option pricing requires the probability distribution of the future asset price, not just the average. They relied on the work of physicist, Albert Einstein, on the Brownian motion of gas particles. It led to the $Trillion Derivatives industry and eventually a Nobel Prize. Although the Black-Scholes formula was not perfect it was vastly better than the alternatives, and those who chose to ignore or justify the harmful practices of using averages were the ones who lost their salaries, often to be replaced by physicists.

Chancification

My recent book on Chancification shows how today, the revolutionary quantification of uncertainty that began in finance can spread to many other sectors without anyone losing their salaries. But how?

Analysts are by and large already quantifying uncertainty but can’t convey it as such in corporate databases, nor would decision makers know what to do with it if they got it. ProbabilityManagement.org has now developed tools and standards to transition organizations into the Chance Age by integrating existing decision-makers, analysts, and IT systems, without requiring any new hires or significant software development. But how?

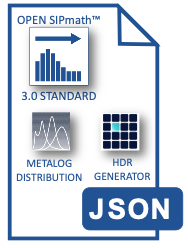

The secret sauce, no make that the open-source sauce, is the SIPmath™ 3.0 Standard, which can convey millions of simulation trials in as little as a few hundred bytes of JSON data, based on the HDR pseudo random number generator of Doug Hubbard, and the remarkable Metalog Distribution of Tom Keelin. JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a common data-interchange format that can be interpreted by humans and machines. It is easy to generate SIPmath 3.0 JSON files from nearly any form of analytics. But how?

Open-source Python code reads standard analytics output through an API (Application Programming Interface) recently developed by the nonprofit. The files produced may be interpreted by virtually any software platform, including native Excel so managers can start making Chance-Informed decisions. But how?

The ChanceCalc Excel add-in, developed by ProbabilityManagement.org, requires a manager to learn only two new commands: Input SIP and Chance of Whatever as shown in the video below.

Give Chance a Chance

Do you want to learn more? Join me for one of my webinars and receive a free copy of ChanceCalc ($150 value). To register, visit Welcome to the Chance Age Webinars.

© Copyright 2023, Sam L. Savage