By Matthew Raphaelson

Chief Financial Officers, Do You Know What is Lurking Inside Your Forecasts?

The well-known Mazlow hierarchy prioritizes human behavior starting with basic survival and ending with self-actualization. A subset of the human species, the Chief Financial Officer has its own hierarchy of motivations, as visualized below:

First on any CFO’s mind, the organization must have enough cash to meet its obligations to employees, vendors, creditors, and the government. Many CFOs will conduct internal earnings forecasts to provide an expected cash position. There is a serious problem with this approach. Just because the expected cash position is positive doesn’t mean that there is no chance of running out of cash. This is an example of the Flaw of Averages.

What is Lurking Inside Your Cash Flow Forecast?

Let us illustrate this problem with a scenario. The CFO recently completed an earnings forecast that projected ample cash to meet all obligations including a $50 million debt payment due at quarter end. The CFO was not informed that lurking inside the forecast was a 9% chance that a large sale would fall through and a line of business would experience severe cost overruns. While the CFO would rather work on optimizing capital allocations to maximize long-term value, suddenly, the CFO is faced with defaulting on the loan or missing payroll. Either way, the CFO is out of a job.

Had the CFO been aware of the chances, the CFO could have taken actions ahead of time to strengthen the cash position. We call these actions the “CFO Levers.”

Cut expenses (operating expenses and capital investments)

Call in accounts receivables early (at a discount of course)

Ask the bank for an increase in the line of credit (LOC)

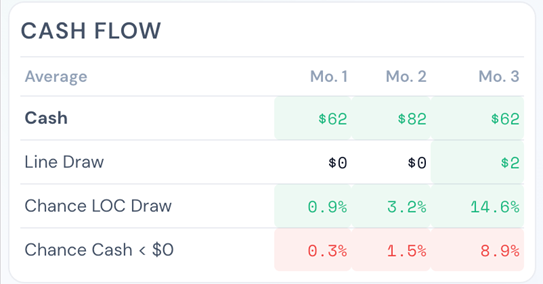

Suppose the forecast has been completed with the results shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1. Static forecast as submitted by lines of business and cost centers. These images are reproduced from the CFO phone app, available using the QR Code above.

By quarter end, the forecast projects $60 million in cash and the CFO is assured of a positive cash position even after the debt payment.

CFO, are you prepared for your career ending soon?

Feeling lucky? Don’t put away your CFO levers just yet.

Everyone knows that forecasts are just predictions, and predicting is hard, especially the future[1]. Most forecasts produce a single-number: “We’ll have $60 million cash at quarter end”. That number is a comfortable lie.

Behind every single-number forecast hides a range of outcomes – some better, some catastrophic. How does the CFO gain access to this range of outcomes?

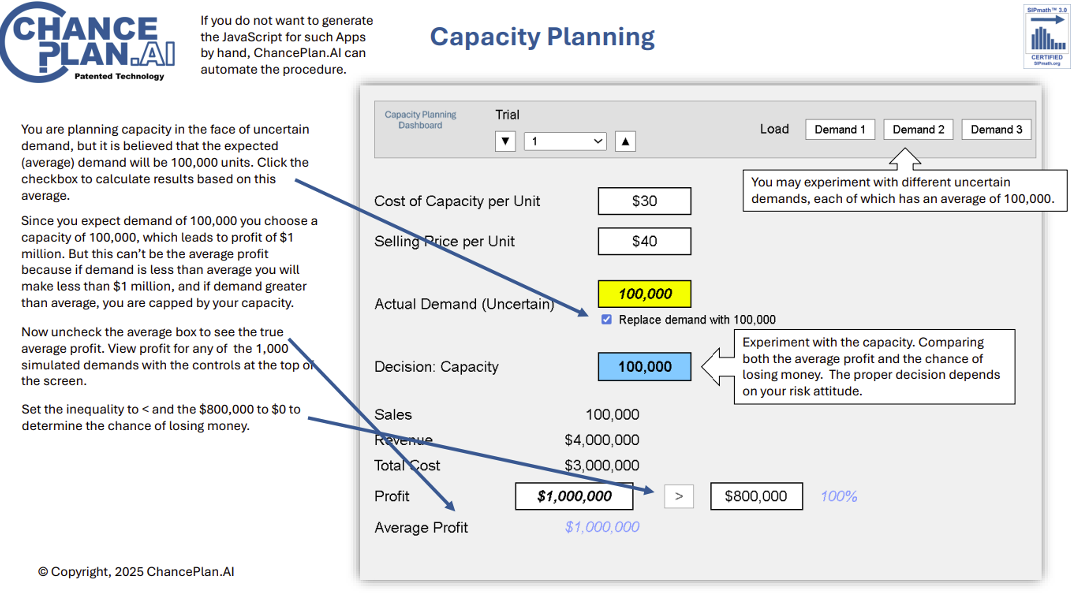

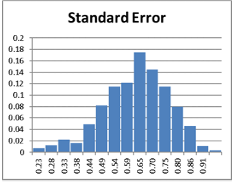

There is a solution. The CFO knows from prior experience how badly forecasts have missed once the actual revenues and expenses are known. AI and other recently developed tools and standards[2] enable today’s CFO to transform static forecasts into stochastic forecasts which, you guessed it, provide the chance of running out of cash by month, as presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Stochastic cash flow forecast based on stochastic data calculation.

The CFO learns that cash adequacy is not assured and there is an 8.9% chance of running out of cash by the end of the quarter. Few CFOs will accept an almost 10% chance of a career-ending event. Time to start working the CFO Levers to avoid a forced early retirement!

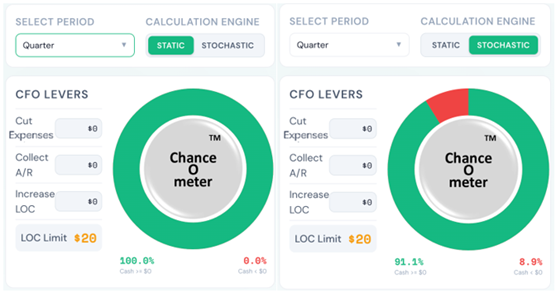

Introducing the Cash ChanceOmeter

The CFO’s decision process can be demonstrated through an interactive ChanceOmeter that provides instant feedback on the impact of moving the CFO Levers. This is based the Open SIPmath™ Standard for stochastic data, which allows the results of Monte Carlo simulations to be combined and distributed across the enterprise for use in Excel, Web apps or even on a phone.

For the submitted forecast, based on single-number estimates, the static ChanceOmeter in Figure 3 below displays a misleading 0% chance of running out of cash and no need to make use of the CFO levers. The stochastic results, which quantify uncertainty, tell a very different story. As we saw earlier, by month 3 there is an unacceptably high 8.9% chance of running out of cash as shown by the stochastic ChanceOmeter in Figure 4 below.

Figure 3. Based on static forecast Figure 4. Based on stochastic data calculations

The ChanceOmeter transforms the CFOs static forecast into a stochastic dashboard. It shows:

The actual odds of running short, by month and for the quarter

What each CFO lever buys in reduced chances of running out of cash

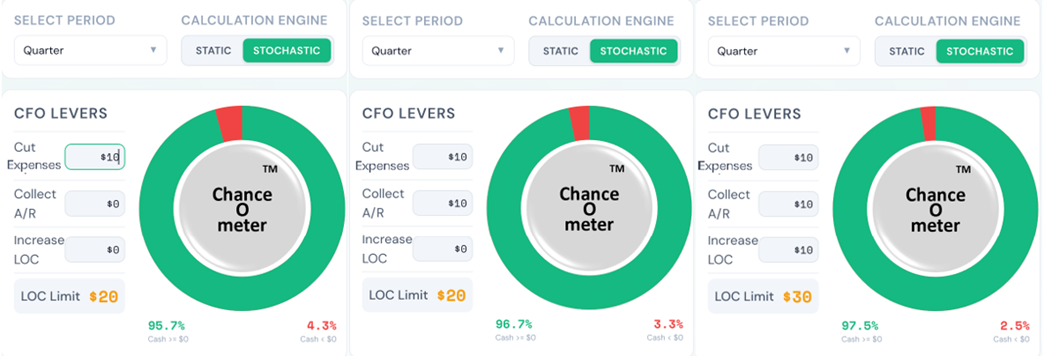

The CFO activates the levers and instantly learns from the ChanceOmeters in Figure 5 below. The CFO understands that there are long-term costs to these levers – foregone future revenues, higher debt service costs, and impacts to employee morale and productivity – and must assess the trade-offs carefully.

Reducing or delaying expenses by $10 million is a powerful lever, reducing the chances of running out of cash by more than half, to 4.3%

Combining the expense lever with $10 million of early receivables further reduces the chances of running out of cash to 3.3%

Increasing the LOC by $10 million on top of the first two levers drives the chances of running out of cash down to 2.5%.

Figure 5. ChancOmeters for reducing expenses; reducing expenses and calling in receivables; reducing expenses, calling in receivables, and increasing the LOC.

All three actions have lowered the chances of running out of cash by over 70%. The CFO understands that the chances can never be 0% and it would be prohibitively expensive to get closer to 0%. The interactive nature of the ChanceOmeters help the CFO assess the tradeoff between the hard and soft costs associated with the CFO levers and reducing the chances of running out of cash[3]. In this case, the CFO accepts the costs associated with a 2.5% chance of running out of cash.

So, How Do You Know Your Chances of Running Out of Cash?

If you are using forecasts or estimates based on single-numbers, you don’t know. There is no excuse for using averages in the age of stochastic data. We call it the Chance Age. Now, any CFO can transform financial forecasts into stochastic data, do calculations in Excel, Python or a Web app, understand the chances of running out of cash, and apply CFO levers.

Some organizations have ample reserves and are not worried about running out of cash; unexpected calls on these reserves are still a black eye for the CFO. Reserves protect against outcomes. They don’t protect against ugly surprises – ChanceOmeters do.

This isn’t just risk management theatre. It’s the difference between “we’ll probably be fine” and “there’s a 2.5% chance we won’t be, and here’s the cost to keep it that low.” CFOs who can quantify that tradeoff don’t just avoid disaster, they allocate capital more intelligently than competitors who are still staring at single-number forecasts and hoping for the best.

The Enlightened CFO

For CFOs in the Chance Age, there are four levels of enlightenment:

1. Honesty: Admit there is uncertainty and stay up at night worrying about it.

0. Ignorance: A solid step down from 1, rely on single-number forecasts imparting a false sense of certainty. Sleep well until your career ends.

2. Awakening: Use stochastic data in your calculations to reveal the chances of success or failure.

3. Enlightenment: Do something! Apply the CFO levers to increase the chances of success without excessive cost!

The CFO who can assess chances and apply the levers to improve them is ready for the higher order motivations on the Maslow hierarchy. Once the chances of running out of cash are understood and addressed, the CFO can focus on meeting earnings estimates, allocating capital more efficiently, and ultimately raising the company’s stock price.

Matthew Raphaelson: Technical Director, ProbabilityManagement.org, Director of ChanceAlytics, ChancePlan.AI. For 25 years Matthew was the CFO for a large financial services business unit with broad experience in finance, data science and risk management. He holds a BA from the University of Michigan and MBA from Stanford University.

Afterword by Dr. Sam Savage

The CFO ChanceOmeter is the culmination of decades of collaboration with three Comrades in Arms in the War on Averages. Matthew Raphaelson, who designed the app, was my student at Stanford in 1991, and for decades performed Chance-Informed analysis as the CFO of a large organization. Doug Hubbard, author of the acclaimed How to Measure Anything series, developed the portable HDR random number generator, which enables cross-platform, distributed stochastic simulation. Tom Keelin’s Metalog distribution is an extremely flexible approach for quantifying uncertainty based on data. I connected the HDR to the Metalog through a data structure called the Copula Layer to create the Open SIPmath™ 3.0 Standard for Coherent Stochastic Data, which obey both the laws of arithmetic and the laws of probability. This work was performed through 501(c)(3) nonprofit, ProbabilityManagement.org, and would not have occurred without its supporters and staff. ChancePlan.AI is a commercial venture whose aim is to apply the open technology of the nonprofit, much as Red Hat applies the open Linux technology.

[1] Paraphrasing a quote attributed to Niels Bohr, Yogi Berra, Samuel W. Goldwyn, and others.

[2] Refer to probabilitymanagement.org for more information on stochastic data, metalogs, HDR pseudo random number generator, and SIPMath standards.

[3] This tradeoff can be quantified and visualized as tradeoff curves. How to do this will be covered in a future article.

Copyright © 2026 Matthew Raphaelson